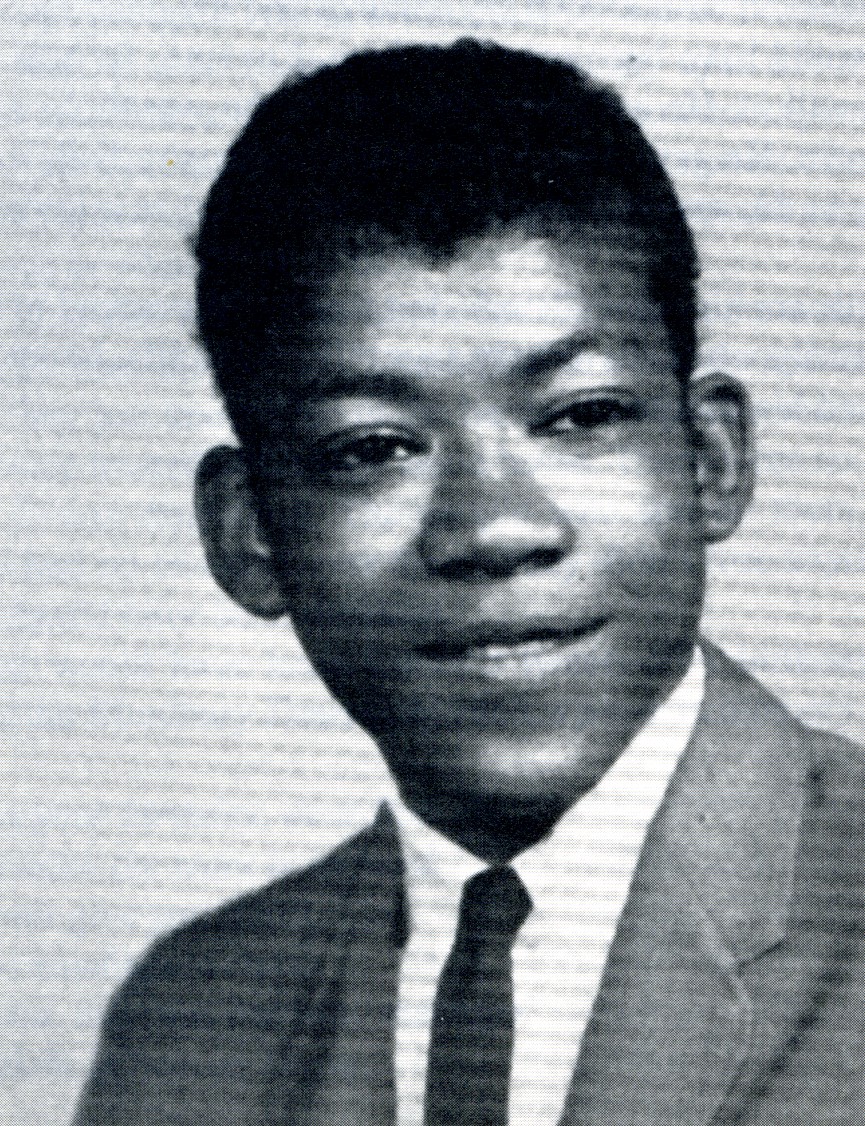

WILLIAM I POLLARD - MSGT

- HOMETOWN:

- swedesboro

- COUNTY:

- Gloucester

- DATE OF BIRTH:

- April 12, 1925

- DATE OF CASUALTY:

- December 04, 1967

- BRANCH OF SERVICE:

- Army

- RANK:

- MSGT

- STATUS:

- KIA

- COUNTRY:

- South Vietnam

Biography

William I. Pollard was born on April 12, 1925. His home of record is Swedesboro, NJ. He served in the US Army and attained the rank of Master Sergeant (MSGT).

Pollard was killed in action on December 4, 1967.

Ike

April 12, 1925 - December 4, 1967

MSGT, Army Swedesboro, NJ

During World War II, the U. S. Army developed a necessary and effective means of rapidly delivering combat troops via parachutes with pinpoint accuracy, sometimes behind enemy lines. The 'Airborne' troopers of the time were heralded by the French as saviors because they were instrumental in the success of the Normandy Invasion that signaled the end of German domination in Europe.

In subsequent decades, airborne divisions played a very important part in the Cold War and its hot spot, Vietnam. 'Airborne' became a battle cry for those elite and highly trained soldiers who took a special pride in their roles as combat assault troops. They were not only infantrymen, they were 'jumpers'. But when assigned to Vietnam or to a regular infantry unit, they lost their 'jump status' and performed as foot soldiers.

Such status eventually became the obsession of William 'Ike' Pollard. Born in Swedesboro, NJ in April of 1925, he was one of eight children of Isaac and Margaret Pollard. His early life was tormented with break-ups and family separations. He attended the old Swedesboro Elementary School until 1939 and then lived with an aunt in Tappahannock, VA. He left school at sixteen and joined the Navy in January of 1944.

The destroyer, USS Decatur-DD 341, became his home for the last two years of World War II. The ship performed convoy duty in the Atlantic and gained a reputation as a 'U-boat' killer. Upon his discharge in 1945, Ike spent two months back home in Swedesboro. The military had evidently been good for him because in February of 1946, Ike joined the U. S. Air Force. He spent two years with an aviation engineer battalion on Guam before being transferred to Eglin Air Base in Florida for the final year of his Air Force enlistment.

In February of 1949, Ike ended his Air Force career and started yet another by enlisting into the Army. He was able to maintain his rank of Sergeant and immediately trained to be a parachutist. By November of 1949, he was a Jumpmaster with the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg, NC.

After almost two years at Fort Bragg, Pollard was transferred to the 11th Airborne Division at Fort Campbell, KY. He attended non-commissioned officers school there and became a Master Parachutist. He also met and married a local girl from neighboring Clarksville, TN. Tragically, she died in July of 1952. Ike continued with the division through its deployment to Germany in March of 1953.

After a short stint in Germany, Ike came back to the states assigned to the 3rd Armored Division at Fort Meade, MD. He spent a year there as an operations sergeant before re-joining the 11th Airborne Division at Fort Campbell. It was there that he met another Clarksville woman named Mary Northington. Their romance blossomed rapidly and they were married in 1954. Mary had two sons from a previous marriage and Ike took on the role of father in addition to his duties in the military.

"He was only about five feet nine inches tall but very muscular," Mary remembers. "He was basically a quiet person but liked to cut up in front of people and being the life of the party. And he was a gung-ho soldier who loved being 'Airborne'. But after we got married, he started to think about it a little. He said that every time he would jump, he could see me riding in a big pink Cadillac."

In March of 1956, the 11th Airborne Division was again airlifted to Germany. And the Pollard family grew as Ike, Mary and the boys were soon joined by Marcia, who was born in January of 1957 and Merion, who was born in February of 1958.

"He was a very good father but I was the 'meanie' of the family," Mary recalls. "He was always protective of the kids and not near as strict as I was. And he always defended those boys, no matter what they did."

Mary also remembers the passion for pinochle that Ike developed, and how she grew to dislike the game. "That was his thing," she says. "Every weekend, it was pinochle. The men would get too excited about it. Ike didn't like to lose and when he did, you would know it."

After attending several leadership schools and being cited as an outstanding non-commissioned officer, Ike was promoted to Master Sergeant. The 11th Airborne Division was deactivated and in December of 1958, the Pollards were on their way back to Fort Campbell where Ike was assigned to the 101st Airborne Division as a jump school instructor.

The Army's need for drill instructors, Ike's military bearing and ability to teach others meshed in his next assignment, Fort Jackson, South Carolina, in September of 1959, where he served in that capacity until July of 1962.

"Fort Jackson was not the best assignment as far as I was concerned," says Mary. "It was not a good time to be black and living in the South. My girlfriends and I would go into Columbia to do some shopping but could not go into the lunch counters at Woolworth's or any of the stores. We basically had to stay on-post most of the time. Even the kindergarten at the base was segregated. Civilians ran it and they were in no hurry to integrate."

The problems faced by the Pollards were compounded by the fact they now had a teenage son who needed a social life. "The teen club at the base was also segregated until Ken and some of his friends made an issue of it," Mary continues. "They were made to feel very uncomfortable when they insisted on being allowed in. The other kids ignored them and made them sit at a table way off to one side. When they tried to leave, they had to pass through two columns of white kids waiting outside for them with chains. Needless to say, there was a big fight that I didn't find out about until much later. It was just as well I didn't know."

Ike detailed the incident to Mary when he came home from daylong meetings with the post commander. "He told me that my boy helped integrate the teen club by fighting it out with the white kids," she remembers. "They were keeping the whole thing hushed up because the club was supposed to have been integrated all along. Ike knew I had a big mouth and was afraid I'd start more trouble. But I said, 'If that's what happened and now things are going to change, I won't say anything.' Ken had some white friends and I know he felt bad about the whole thing, but all of a sudden, all the kids could go there and have a good time. There was never anything about it in the post newspaper."

After two years at Fort Jackson, Ike was transferred to the 25th Infantry Division in Hawaii. They were to be there for three years and while the kids may have liked it, Mary was not impressed.

"I'm not much for pineapples and sand," she says. "We couldn't really do all that much."

When the three years were up, Ike requested a transfer to either the 101st Airborne Division at Fort Campbell or the 82nd Airborne Division at Fort Bragg. He had lost his jump status serving with the 25th Infantry Division and wanted it back.

"Airborne troops were spit-and-polish," Mary says. "He was always in the mirror and would keep asking me how good looking I thought he was. Ike maintained that image, even as a 'leg' soldier, but longed to be jumping again. He really wanted another 'Airborne' assignment."

By August of 1965, the Vietnam War was demanding more and more trained troops. Ike was a good drill instructor, so the Army assigned him to a basic training unit at Fort Polk, Louisiana.

"There was no way I was going to take my kids to the deep South again," Mary says. "There was too much going on with the civil rights movement and we would have been restricted to the base again."

While on leave, Ike made a visit to the Pentagon and managed to get his assignment changed to Fort Dix, NJ, as a drill sergeant and was able to move his family there. He could have retired with more than twenty years of service after his tour was finished at Fort Dix. Instead, Ike volunteered for Vietnam duty in January of 1967.

"He was afraid more of getting out of the service than he was of the war," Mary says. "The military was his whole life. He knew nothing else and was good at what he did. And every time he was up for re-enlistment, he would say 'This is my last time. I'm getting out after this tour.' I told him once that if he ever did get out, I was going to divorce him anyway. He would have driven me crazy. And he did not like the idea of taking orders rather than being in charge of something all the time."

In July of 1967, Ike left for Vietnam and his family moved into an apartment in Mount Holly. Mary worked at the Post Exchange at Fort Dix while Ike joined the 4th Infantry Division, based near Pleiku, in the central highlands of South Vietnam.

For the first four months, he served as a platoon sergeant with the 1st Battalion, 22nd Infantry Regiment of the 4th Division. He was then transferred to the 9th Infantry Division and the Army's half of the Mobile Riverine Force in the Mekong Delta.

The Second Brigade of the 9th Infantry Division fulfilled the requirements of a combined strike force that could operate in the many rivers and inundated rice paddies of the Mekong Delta. The troops lived on barracks ships that were docked at the anchorage at Dong Tam, and would be transported by water on Navy Armored Troop Carriers. This amphibious force operated entirely afloat, a far cry from the Airborne assaults Ike spent most of his career preparing himself and others to take part in.

After only two weeks with his new unit, Company A, 3rd Battalion, 47th Infantry, Ike Pollard was serving as a Platoon Leader on a search and destroy mission in Dinh Tuong Province, deep in the Mekong Delta. His military career had come full circle. It began on a combat ship in the Navy and now Ike was being delivered into combat, not by flying or parachuting in, but by another Navy vessel. His posthumous Silver Star citation reads:

As the unit proceeded down a jungle tributary aboard Armored Troop Carriers, a portion of the element came under intense rocket fire from a determined Viet Cong force. Upon landing, Sergeant Pollard began leading his men through an area of dense vegetation toward the enemy position. Suddenly the point element came under a torrent of automatic and semi-automatic weapons fire from a well entrenched Viet Cong force. Without regard for personal safety and fully realizing the peril of the situation, Sergeant Pollard aggressively led his men forward through a hail of enemy fire to a position where maximum firepower could be achieved against the insurgents. Seeing that several of his men were pinned down and unable to move, Sergeant Pollard gallantly volunteered to lead a portion of his platoon forward in an effort to alleviate the pressure exerted by the guerillas on his men. While performing this courageous act, Sergeant Pollard was mortally wounded. Master Sergeant Pollard's extraordinary heroism is in keeping with the highest traditions of the military service and reflects great credit upon himself, the 9th Infantry Division and the United States Army.

Mary Pollard was to suffer another devastating loss in 1985, when her daughter, Merion, died. Since then, she and the three surviving children have grown in many ways. They have 'made their own way' and have become outstanding citizens in the process. Mary's faith keeps her on course and she displays her sense of humor with a poster that she keeps in her kitchen; Lord, Give me patience and I want it now!

She wants Ike to be remembered, "as he lived...he was not a saint but he was a good father, a good husband and above all, a good soldier."

"I always thought he would be the one to make it back," Mary says now. "He had such a cavalier attitude about the war. He would joke about it before he left. He sure came back, but not the way I thought he would."

Excerpt from They Were Ours: Gloucester County's Loss in Vietnam

by John Campbell

Used with permission of author

Information provided by NJVVMF.Remembrances

Be the first to add a remembrance for WILLIAM I POLLARD

Help preserve the legacy of this hero, learn about The Education Center.

LEARN MORE